Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, when Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, and informed slaves that there that they were free.

The cruel irony was that, thanks to the slow pace of 19th century wartime communication, slaves in the South had been freed over two years prior by President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The date now serves as a triumph of the human spirit. It’s the official recognition of the survival of enslaved African Americans who were subjected to the most inhumane of conditions and yet made immeasurable contributions in building this country.

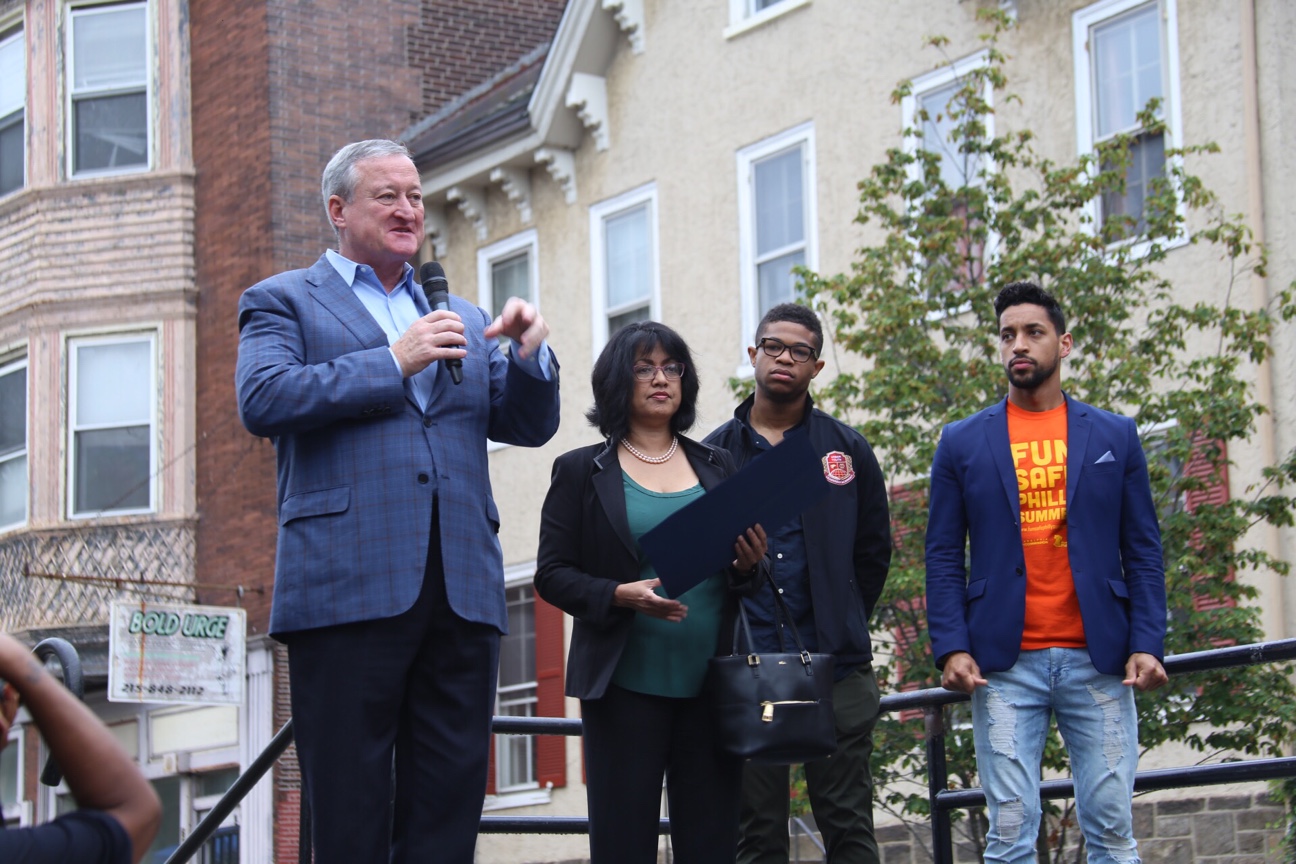

Here in Philadelphia, Juneteenth celebrations take place, most notably in Germantown near the iconic Johnson House, described as “Philadelphia’s only accessible and intact stop on the Underground Railroad.” The extensive network of clandestine routes and safe houses had stops, and leaders, across the city.

Against enormous odds, when even learning to read and write was a criminal act, African Americans persevered in charting their own destiny, fighting for freedom and equality. One of the most famous freedom seekers, Harriet Tubman, often called “the Moses of her people,” was a conductor on the Underground Railroad and had a large bounty of on her head for escorting over 300 freedom seekers over a 10-year period, beginning around 1850, out of the American South.

She reported that she made 19 trips and insisted she never lost a passenger on the way.

Many other African American women, like Sojourner Truth, played a significant role in the abolition movement, too.

In Philadelphia, women such as Sarah Mapps Douglass and the Forten family women founded an integrated organization with white Quakers, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. They organized fairs to raise awareness and revenue to fuel the abolition movement, circulated petitions, wrote letters and poems, and published articles in the leading anti-slavery periodicals such as “The Liberator.”

William Still, another prominent conductor on the Underground Railroad, was born a free person in New Jersey and moved to Philadelphia where he was very active in the abolitionist movement. His parents were former slaves.

Still, a clerk, had a fastidious writerly instinct. He kept meticulous records documenting much about the Underground Railroad system along with the personal experiences of many freedom seekers. Later, he published these records as “The Underground Rail Road: A Record.” This invaluable trove of information paints a picture for us about the hardships, narrow escapes, and the death struggles involved in the path to freedom.

This journey to freedom was aided and abetted by white abolitionists, many of them Quakers who provided the safe houses along the Underground Railroad.

The Johnson House, located at 6306 Germantown Avenue, is one of those safe houses. During the 19th century, and for several generations beyond, the home was owned by a family of Quaker abolitionists who worked with African Americans, free and enslaved, to secure safe passage. It’s long been rumored that Harriet Tubman once stopped there.

A present-day visit to the Johnson House allows us to contemplate the anxieties of those seeking freedom; it was a profitable venture to apprehend a freedom seeker since there were bounties on their heads. And, for those harboring a “fugitive,” federal charges, including treason, could follow.

Notwithstanding these horrific obstacles, thousands overcame the challenges and pursued their rights and dignities as human beings regardless of the possible cost.

Celebrating Juneteenth is a reminder of the bravery and resilience of a people who rejected the yoke of slavery and, then later, Jim Crow.

It is a joyful celebration for all Americans to rejoice in the correction of the course to a “more perfect Union” and a commitment to liberty and equality.