In celebration of Native American Heritage Month, I reflect on the stories of struggle, resilience, and survival that honor the Native people who occupied and stewarded the land we live on today. The history of Native people is more than academic for me—it’s personal. As someone of African and Native heritage, I take pride in my multicultural identity.

Growing up in North Philadelphia during the late 80s and 90s, I was exposed to a rich mix of cultural traditions inside my home. My father instilled a deep respect and pride for our Black and African heritage, teaching us that brilliance transcends skin color, economic status, and family dynamics. My mother, a board member and secretarial officer of the United American Indians of the Delaware Valley, Inc. (UAIDV), and a member of their women’s singing group, Kanahoochie (Tuscarora), familiarized me with my Native heritage. When I was a child, she shared details of my ancestral lineage and brought me to pow-wows, intertribal dances, and gatherings where goods and folklore were exchanged. As an adult, I have participated in panels with Native Chiefs and visited sacred lands across the country, and I try to pass along the lessons learned to my daughter.

Additionally, my mother shared stories of family elders who preserved our traditions despite incredible challenges. One of these elders, my great-grandmother, was born on a reservation. Her legacy taught me the importance of remembering and honoring my history. Part of this history includes the creation of Federal Indian Boarding schools (also known as “residential schools”).

A History We Cannot Ignore

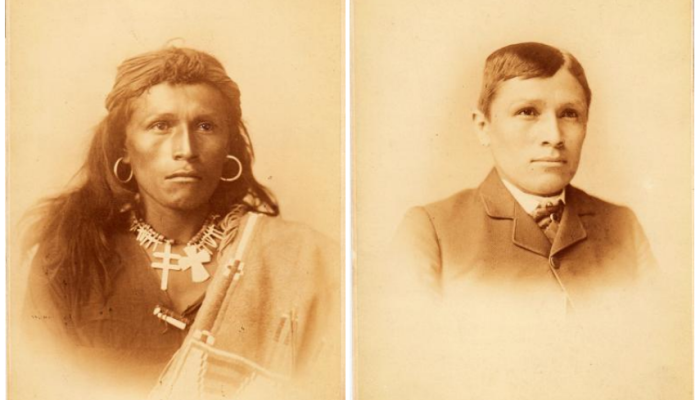

First established in 1819, Federal Indian Boarding Schools aimed to erase Native cultures and communities and support westward expansion. Their main goal can be summed up in the phrase “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” One such boarding school, Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School (founded in 1879), became the model for approximately 523 similar schools nationwide.

According to a 2024 investigative report by the U.S. Department of the Interior, native children faced harsh conditions in these boarding schools, including physical abuse, malnutrition, and forced labor. Their hair was cut, and their native languages, clothing, and traditions were forbidden in attempt to erase their culture. Discipline was cruel, with punishments such as belt beatings, forced kneeling on broomsticks, and lye soap in the mouth that caused painful blisters. Some children were even pinned through the tongue to prevent them from speaking their native languages.

Days at these schools were split between classroom lessons on Western culture and hard manual labor that helped to develop American Western industries such as mining and ranching. Boys worked as carpenters and shoemakers, while girls learned domestic tasks like sewing and housekeeping. But these skills did not prepare students for meaningful futures in the job market. Instead, they left generations of Native communities economically disadvantaged, disconnected from their cultures, and grappling with deep trauma.

According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, hundreds of thousands of Native children were taken from their homes and placed in these schools between 1869 and the 1960s. The total number of child removals is unknown, but by 1925, nearly 61,000 Native children were enrolled in boarding schools. The U.S. Department of the Interior has confirmed at least 500 known deaths, although the actual number of deaths is likely much higher. The trauma caused by these policies affected not only the children placed in these boarding schools, but also reverberated across generations, destabilizing families and communities. It left a lasting impact and shaped the foundations of the current child welfare system in the United States.

“Our children had names, our children had families, our children had their own languages…Our children had their own regalia, prayers, and religion before boarding schools violently took them away.” – (Deb Parker, Chief Executive Officer of the National Native American Boarding School Association)

In her 2022 book, Torn Apart, author Dorothy Roberts connects the use of Federal Indian Boarding Schools in the 19th and 20th centuries to the child welfare system in the United States. It must be noted that the combination of forced assimilation, cultural erasure, system-wide genocide, and involuntary child labor is unique to the experiences of Native youth in Federal Indian Boarding Schools. However, Roberts highlights that the removal of Native children from their tribes is an essential part of the history of today’s child welfare system, which is “rooted in settler colonialism as well as slavery,” and disproportionately impacts marginalized communities. This perpetuates a cycle of separation and systemic disadvantages.

Land Reflection

Today, Black and Latinx youth involved in the child welfare, juvenile justice, and behavioral health systems are disproportionately placed in youth residential placements facilities across Philadelphia. This city, like much of this country, occupies land originally cared for by Native peoples. Recognizing this history means acknowledging the ongoing impact of systems that fail to center care and accountability.

The Office of the Youth Ombudsperson (OYO) honors this history in its land acknowledgement, which is a traditional custom that dates back centuries in many Native nations and communities:

“For centuries, the land now known as Philadelphia was home to and cared for by native peoples. These include the Lenni-Lenape People of Lenapehoking and the Poutaxat (Delaware Bay). We recognize these Tribes’ strength and history of resistance to colonization. We commit to honoring their history, presence, and future. We support local Native people, including:

– The Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation

– The Ramapough Lenape Nation

– The Powhatan Renape Nation

– The Nanticoke of Millsboro Delaware

– The Lenape of Cheswold Delaware, and more.”

The OYO honors the impact that land dispossession has had on Native communities and strongly supports the call to return former Federal Indian Boarding School sites and original tribal lands to Native nations. For more on this topic, see the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which includes an investigative report with recommendations, a listening tour for Native survivors, and an oral history project documenting Native children’s experiences.

A Call for Reflection and Action

As we reflect this season, let’s remember the stories of those who came before us, the challenges that youth in care face today, and our shared responsibility to honor and learn from history. The story of Native boarding schools reminds us about the harm caused by removing children from their communities, but it also shows the power of resilience and the importance of strong, connected communities.

Today, these lessons resonate in the ongoing work to support youth in placement, where systems often fail to fully recognize youth identities and experiences. At the OYO, we work on a local level to amplify youth voices, center youth stories, and prioritize youth well-being. By collaborating with the community, leaders, and youth themselves, we aim to create a system that truly supports and values young people in care. At the national level, advocates are working to protect the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which is a federal law that establishes standards for the removal and placement of Native children. Advocacy for ICWA is critical in stabilizing Native families and communities and protecting their rights.

We encourage readers to join those already doing this important work – you can educate yourself on Native history, explore resources from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, support survivors, familiarize yourself with our office, and advocate for justice. Let’s honor the truth this season—not to divide, but to inspire. Let’s listen to the stories of the past, uplift voices from the present, and commit to a future where every child feels valued and supported. Together, we can carry these lessons forward to build a brighter future for all.