Philadelphia Parks & Rec has 26 sites named in honor of African Americans. But only one site is associated with three notable Black figures.

Charles T. Mitchell, Jr. Park, home to the Seger Recreation Center, is associated with three notable Black figures. The naming of the park reflects racial, class, and political power struggles of its time.

In the early 1900s Philadelphia was leading the way building new play spaces in the city. Quality recreation spaces were seen as a way to improve the lives of residents. In 1916, the City purchased the block bounded by 10th, Rodman, 11th, and Lombard streets. The plan was to tear down all the buildings and build a new playground. The site sat in the center of the Seventh Ward, the city’s historic Black neighborhood.

Equity Hall, an important Black meeting space at 1026 Lombard Street, was to remain in the middle of the site. The hall began as a Black Odd Fellows Lodge in 1894. It hosted receptions, banquets, meetings, balls, boxing matches, concerts, and political rallies.

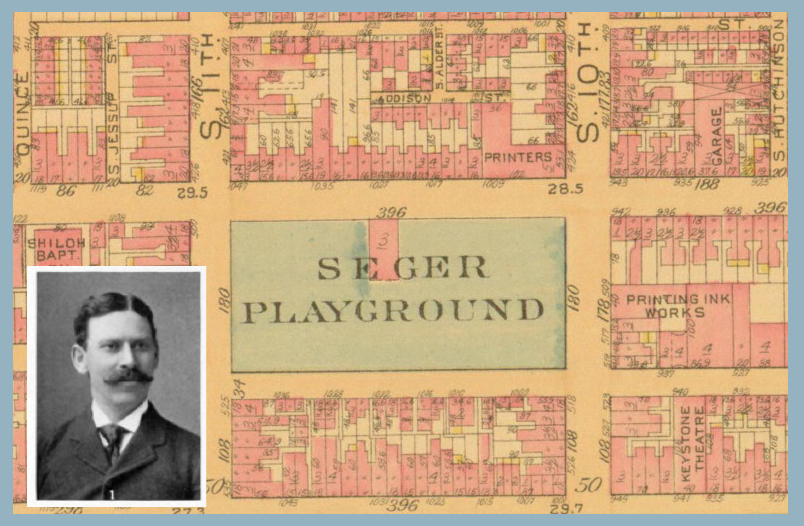

The creation of the park was led by Councilmember Charles Seger. He was a longtime leader in city politics and the Jewish community. He was also viewed as an ally of the Black community. Seger died in 1919. His friend and protégé Charles Hall succeeded him on City Council.

World War I stalled the construction of the park. The city-owned block gained the label “Hell’s Half Acre.” Some religious and political leaders decried the area’s gambling, drugs, and prostitution. Many blamed city leaders for the conditions.

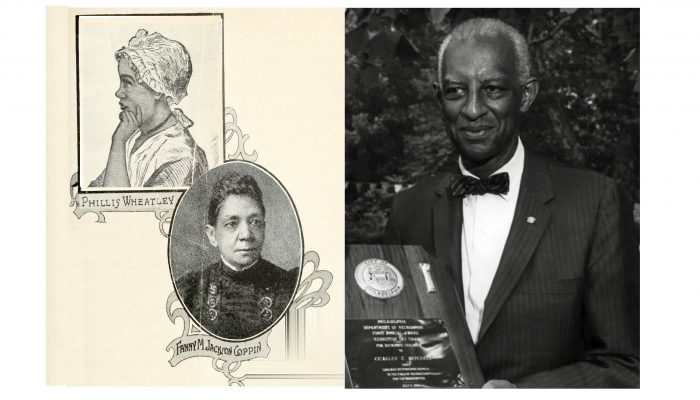

Phillis Wheatley

In 1920, Mayor J. Hampton Moore pushed for the demolition of the homes on the site and the construction of the park. This was partly an attempt to increase his power in the Black community. The Mayor proposed naming the park in honor of Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784) of Boston. Wheatley was a former slave and the first Black poet to achieve international fame.

Mayor Moore’s proposed name started a bitter battle with Councilmember Hall. Hall had planned to name the park after Charles Seger, “the man who made it happen.” He insisted the Mayor had no right to name the park. He said it was the roll of City Council.

Many in the Black community decried being used as pawns by the Mayor in his attempt to expand his power. The Philadelphia Tribune, a renown Black newspaper, said the Mayor was “devoid of any genuine interest in the progress of our people.” Some Black political and community leaders made calculated moves to support Councilmember Hall. This helped secure political support for Black Republican leaders.

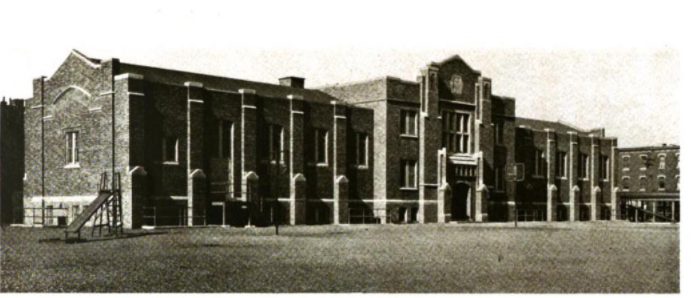

In the end, City Council overrode the Mayor and named the park after Seger. Soon after, Hall secured funding to tear down and replace Equity Hall. In its place rose a new, two-story modern community center.

Frances (Fanny) Jackson Coppin

Hall had the building named after another famous Black woman—one from Philadelphia: Frances (Fanny) Jackson Coppin. Jackson Coppin was a former slave who became a renowned Black educator and community leader. In 1869 she was appointed principal of Philadelphia’s famed Institute for Colored Youth. This made her the first Black principal in the nation. She ran the Institute, now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, for 37 years.

Charles T. Mitchell, Jr.

The Coppin recreation center was expensive to maintain and fell into disrepair. In 1974 the City replaced it with a smaller building. The new building was not given an official name at first. A 1976 city ordinance proposed renaming the entire site. The new name would honor another prominent African-American: Charles T. Mitchell, Jr.

Mitchell was a beloved recreation and civic leader. He was also an important figure in the history of Philadelphia recreation. Mitchell started working at Seger Park in 1928. He became one of the recreation department’s first Black supervisors.

In 1947 he helped desegregate Philadelphia hotels through an agreement with the mayor. In 1952 Mitchell proposed and developed new recreational activities for people with disabilities. He became a tireless advocate for the disabled, serving on the boards of local, state, and national organizations for many years. Mitchell retired in 1971 and passed away in 1976.

Some in the community were reluctant to change the park’s longstanding name. A 1977 ordinance created a compromise. The recreation building was named in honor of Charles Seger. The park was officially renamed in honor of Charles T. Mitchell, Jr.