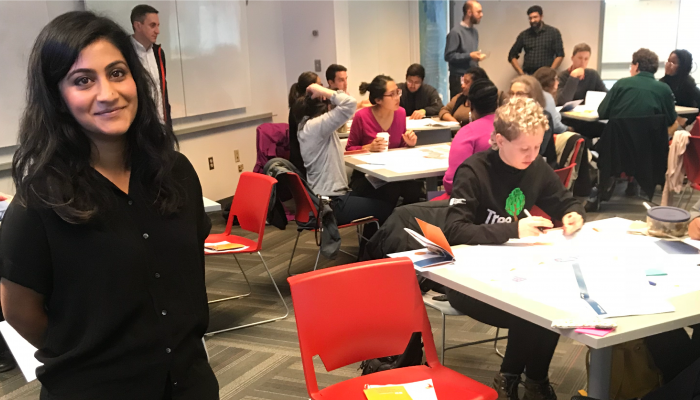

Our work at the PHL Service Design Studio is built on the early advocacy and labor of colleagues who preceded our launch. This post honors one of those colleagues: Aditi Joshi.

Aditi was a service design fellow from October 2018 to January 2019. She worked on a trauma-informed service design project with the Office of Homeless Services (OHS). We recently caught up with her. Below is an edited version of our conversation.

When you were a service design fellow on our team, what did you do?

ADITI: I participated in a project to redesign OHS’s prevention, diversion, and intake service. Through intake, OHS social work staff offer resources, like rental assistance and shelter beds, to those experiencing houselessness. Because participants often show up in crisis, OHS was looking for ways to meet the most immediate needs of participants and those who support them.

Before I joined, the service design team conducted in-depth research and identified several key intervention areas. One of those areas was to ensure participant and staff interactions were trauma informed. As a service design fellow, I helped craft co-design activities with OHS frontline staff and leadership — with the advisement of Dr. Meagan Corrado who’s a licensed clinical social worker — to determine the nature of those interactions.

We created holistic service journey maps to document the recommendations. The maps visualized key moments within the service experience and provided suggestions on how each moment could be more trauma informed. Also, the maps helped OHS leaders understand how the service could work on the ground and gave them concrete steps for implementation.

You designed and facilitated a learning session for over 50 City employees across local government. Tell us about that learning session.

ADITI: Building capacity internal to City government was a core part of the team’s overarching work. The team designed and facilitated eight learning sessions throughout 2018. They were a way for us to take some of our service design know-how and offer colleagues tools to practice themselves.

The learning session I facilitated was focused on equity-centered design. Inspired by the Creative Reaction Lab, equity-centered design acknowledges that people have been disadvantaged by inequitable systems and structures — by design. As a result, we should work to redesign them in ways that center equity.

This framing is a vital mindset for colleagues working in government as government has created and deepened inequities based on race, class, and gender. Equity-centered design encourages colleagues to confront the power dynamics at play in our work, so we can dismantle inequities.

My hope with this session was to help my government colleagues better understand the basic principles of equity-centered design and equip them with tools to experiment on their own.

What’s one thing you took away from your time at the City of Philadelphia?

ADITI: My work at the City taught me to show up for my team members, colleagues, and design collaborators in ways that were caring and trauma informed (e.g., practicing what we preach). This ethos carried through to our work when designing services. Meaning, we actively challenged the practice of crafting paternalistic and means-tested policies that wrote some individuals in and left others out.

I learned how to recognize individuals as products of their lived experiences and of systems of oppression rather than individuals shaped only by their innate characteristics. I have taken this mindset into the work I do now as well as into my own personal relationships — trying to show up with intentionality, reciprocity, and care in interactions with others.

What have you been up to since finishing your fellowship?

ADITI: I’ve been working as a qualitative researcher at a national civic technology non-profit, Code for America. Specifically, I’ve been working on the Clear My Record project, where we’re automating record clearance across the United States.

I focus on having conversations with those living with convictions to better understand their specific needs. And I use insights gathered from these conversations to develop policies and services that shrink the scope of the criminal legal system — seeking to repair some of the harms the system has caused. Also, I collaborate with government stakeholders to understand how current systems are working in practice and how we can make changes for better service delivery.

In addition, I work as an abolitionist organizer with Defund SFPD Now. My work with the City of Philadelphia made me realize how important it is to be in community with those around you. My organizing work with Defund SFPD Now is a way for me to bring my values around shrinking the criminal legal system into a local context that centers community care.

What’s one wish you have for the future of civic design?

ADITI: As designers who work in or with government, we must recognize our positionality and power. We have a responsibility to share power with those who are impacted by what we do but don’t have official pathways to rethink government service delivery. We must continuously confront our power and privilege — especially since the design field is overwhelmingly upperclass and white, while government services (due to systemic inequities) serve low-wealth, marginalized communities of color.

Also, to practice what we preach, as civic designers we should seek to make our internal work environments mirror the world we want to see externally.

I hope that civic designers can help government come to terms with its racist legacy and the way this legacy harms communities today. In doing so, we can build policies, services, and practices that are equitable and help communities begin to heal from the harms of the past and the present.