This post is part of a series called By the people. It explores how the Office of Homeless Services (OHS) and the Office of Open Data & Digital Transformation (ODDT) are using participatory service design methods to improve the City’s homeless prevention, diversion, and intake services. If you’re new to the series, begin with our first post.

In our February post, we discussed what we mean by people-centered. In this post, we outline the processes we used to keep people’s lived experiences at the center of our work with OHS.

How did we do that? We often use the following quote by documentary filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha to describe our participatory design work.

The story depends upon every one of us to come into being. It needs us all, needs our remembering, understanding, creating what we have heard together to keep on coming into being. The story of us.

We appreciate Trinh’s use of filmmaking tools and techniques to shift the power dynamics between herself as a documentarian and the subjects of her films. She doesn’t view the people who are in her documentaries as passive objects of study, but as active participants in the telling and creating of their own stories in collaboration with her. They’re part makers, part creators, and part authors.

As service designers, we use participatory design methods, tools, and techniques to shift power dynamics. We invite input from those closest to the service challenge—like participants and front-line staff—who are often excluded from decision-making. We welcome them as part makers, part creators, and part authors of the change they seek.

Let’s discuss how we cultivated the story of us in our work with OHS participants and staff.

Laying the groundwork

Before we started this project, the PHL Participatory Design Lab team committed to a set of values. We pledged to:

- Focus on people.

- Be humble, listen intently, and respond.

- Act ethically and address inequity.

- Base decisions on evidence.

- Work in the open and with rigor.

- Enable a culture of creativity and the use of non-traditional approaches.

- Design unexpected and beautiful experiences.

- Foster reciprocal relationships.

That last point was especially important as we convened and guided stakeholders throughout the course of our project work with OHS.

Fostering reciprocity

When a service designer asks for feedback, they should be willing to address the feedback they receive. That’s true even if the answer is: “We couldn’t do what you asked for. This is why.” It can be more harmful to ask for someone’s opinion and not respond than to never ask in the first place.

Why? Some of our residents and staff feel over-studied, evaluated, and researched. Others feel that one-off interactions don’t capture or address the complexities of their work or experience. And unfortunately, many report that when they give their opinion, they don’t see results.

These experiences have consequences. Residents can withdraw from participating in government, while staff can withdraw from service improvement efforts.

When you engage people in design research, you should be ready to listen, respond, and demonstrate meaningful change. In order to do that, we committed to the following practices:

- Provide people with a clear entry point into our work.

- Follow up with people after engaging with them.

- Bring people along throughout the process.

- Take action on feedback.

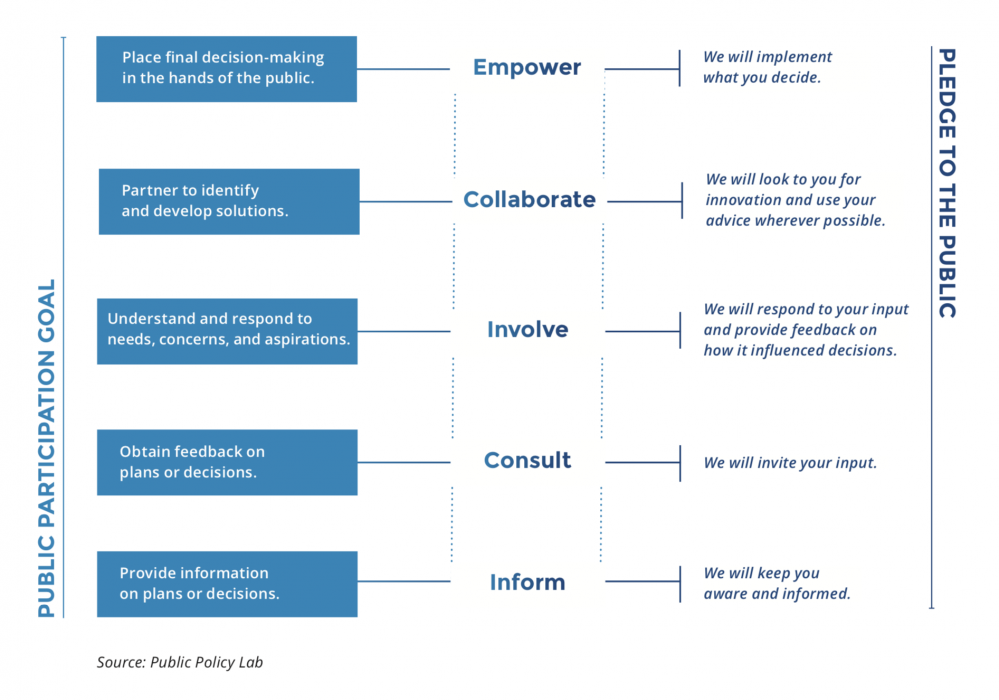

We used the ladder of stakeholder participation to help us follow through on our commitment to foster reciprocal relationships.

The ladder of stakeholder participation

When you’re committed to cultivating a story of us, repairing strained relationships, and driving organizational change, how and when you include stakeholders in the design process is as important as the end result.

We believe intentional participation and processes yield the development of intentional products and services. We used a tool called the ladder of stakeholder participation to think through the different ways stakeholders can be active participants in the design process.

Each rung maps a public participation goal and a pledge by the government (or by us, as public sector service designers). We make these promises to stakeholders who may not have decision-making power, but whose voices and input are important to the project’s success.

Our work with OHS was primarily situated in the Involve and Collaborate rungs. It was important for us to define the levels of participation and any constraints, so we could set clear expectations with stakeholders. We had to figure out:

- When are we looking for input?

- When are we interested in brainstorming ideas?

- When do people have decision-making power?

- When are we simply sharing information?

If you’re clear on the answers to these questions, then those who are eager to participate in design work will be equally clear. Clarity is key to avoiding stakeholder frustration. Clarity also allows for ethical interactions between public sector service designers and design participants.

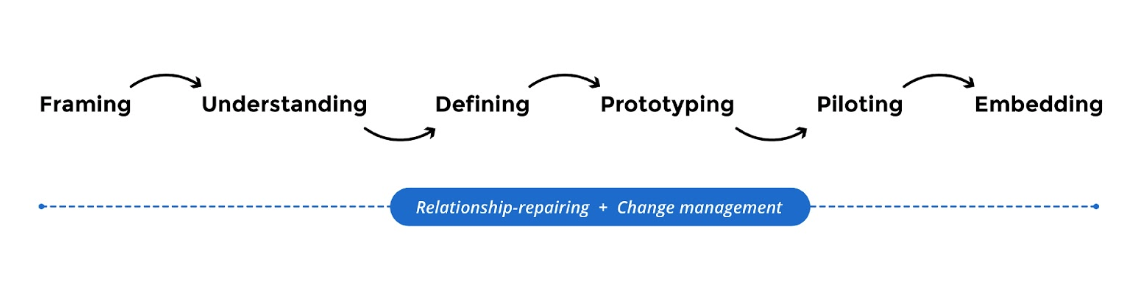

Our participatory design process

Through our participatory design process, we could intentionally collaborate with a host of stakeholders from the beginning of the project to its end, or from design research to implementation. We used the ladder of stakeholder participation to determine what level of collaboration was required by stakeholders at each phase of the design process.

Let’s focus on the first two phases for now.

In the framing phase, we facilitated listening sessions with OHS prevention, diversion, and intake leaders and domain experts. This helped us better understand the challenges we should address. We clearly defined the problem space and scope of work during this phase.

Next, in the understanding phase, we performed design research or deep fieldwork to understand people’s current state experiences with OHS’s prevention, diversion, and intake service from multiple viewpoints. Insights gathered during this phase informed the rest of the project work, from the defining to embedding phases. We’ll discuss this topic in the April blog post.

Returning people’s stories

During the understanding phase, the service design team was in the field for around three months with people experiencing homelessness, people refusing services, front-line staff, service partners across the provider network, and leaders. We facilitated one-on-one interviews, observed the flow of access point spaces, and shadowed staff on-the-job.

We collected a lot of data. We documented many stories. Some service designers harvest this type of qualitative data and move directly into designing a solution. They fail to circle back and include the people who contributed insights. For us, it was important to synthesize what we heard in the field with staff input from across the provider network. They could add nuance to our analysis, challenge any biases, and confirm our understanding of the issues at hand.

Returning people’s stories ensured that staff felt like active participants in the telling and documenting of their own stories—part makers, part creators, and part authors.

The story of us.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In our next blog post, we’ll walk you through some of what we learned during the first several phases of the project. We’ll also discuss how those insights informed the direction of service improvement projects with OHS.

Questions or comments? Email oddt@phila.gov.